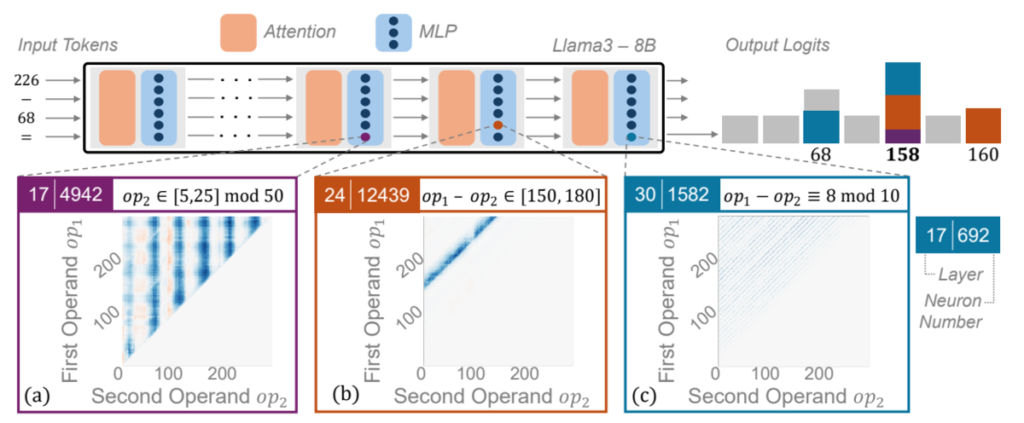

LLMs can answer prompts like “226-68=” by outputting “158”, but it turns out that this computation is carried out in a much stranger way than we might imagine, as shown by [Nikankin+ ICLR 2025].

Let us first confirm the assumptions. We do not use chain-of-thought. We consider the setting where the model directly outputs an answer like “158” to a prompt like “226-68=”.

As a concrete example, consider Llama3-8B. The Llama3 tokenizer assigns a single token to each number from 0 to 1000, so when we input “226-68=”, the next token is chosen as the most probable one among tokens like “0”, “1”, …, “157”, “158”, “159”, …, “1000”.

The key finding of [Nikankin+ ICLR 2025] is that Llama3-8B solves these arithmetic problems by evaluating many coarse conditions about the input and the result, and stacking up their effects.

For example, when we input a prompt template of the form “{op1} – {op2}” (where {op1} and {op2} are filled with concrete numbers),

- Neuron 12439 in layer 24 fires when the result of {op1} – {op2} lies between 150 and 180 -> when it fires, it increases the output probabilities of tokens “150”, “151”, “152”, …, “179”, “180”.

- Neuron 1582 in layer 30 fires when the result of {op1} – {op2} is congruent to 8 modulo 10 -> when it fires, it increases the output probabilities of tokens “8”, “18”, “28”, …, “998”.

and so on.

For instance, if we input “226-68=”, the true result 158 lies between 150 and 180, so neuron 12439 in layer 24 fires and raises the probabilities of tokens “150”, “151”, “152”, …, “179”, “180”. Also, since 158 is congruent to 8 modulo 10, neuron 1582 in layer 30 fires and raises the probabilities of tokens “8”, “18”, “28”, …, “998”.

In this process, tokens like “150” or “998” also have their probabilities increased. However, compared to the true answer “158”, the number of times they get boosted is small. The true answer “158” gets boosted every time, so after accumulating contributions from all neurons, token “158” ends up with an outstandingly high probability.

Each neuron does not solve arithmetic exactly; it only checks a coarse condition. But an enormous number of coarse conditions are stacked, and the true answer is highlighted. The authors call this mechanism a bag of heuristics.

In general, neurons that fire only when {op1}, {op2}, or the result matches certain patterns are called heuristic neurons. The paper considers the following types of heuristic neurons:

- Range heuristics: the value lies in an interval [a, b].

- Modulo heuristics: the value satisfies value mod n = m.

- Pattern heuristics: the value matches a regular expression such as

1.2. - Operand-equality heuristics: {op1} = {op2} holds.

- Multi-result heuristics (used only for division): the value belongs to a set S, where S has 2 to 4 elements.

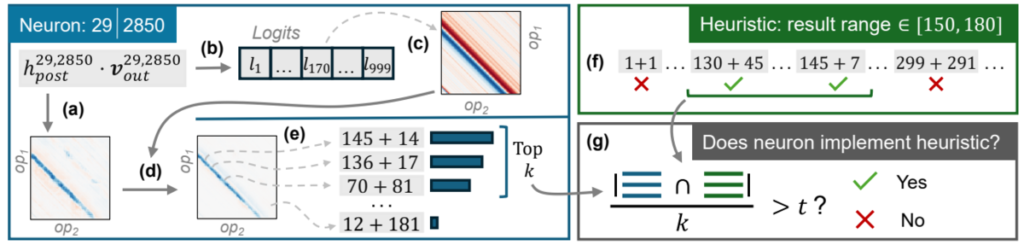

To test whether a neuron is a heuristic neuron, we can input many prompts of the form “{op1} – {op2}”, record when the neuron fires strongly, and then measure how well that activation pattern matches candidate heuristic patterns.

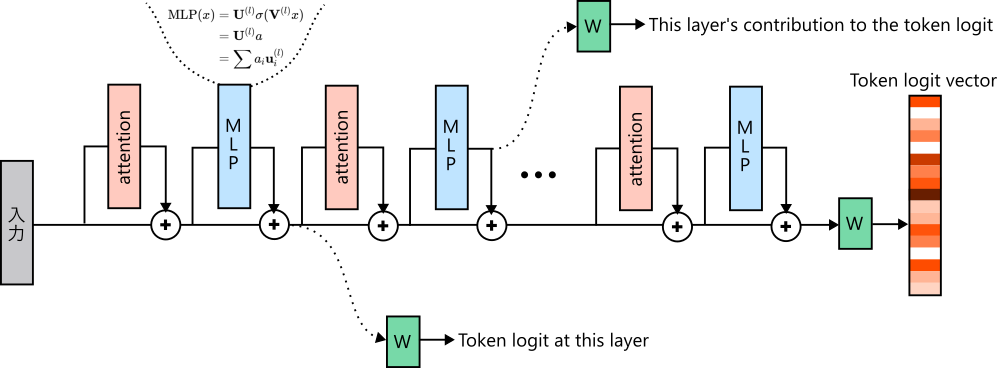

Each neuron’s contribution to the output can be computed using a method called the logit lens [nostalgebraist 2020].

A transformer stacks attention mechanisms and multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) with residual connections. That is, the input to the final linear layer, \(v \in \mathbb{R}^d\), is the sum of the outputs of attention and MLP blocks across layers, \(v = \sum_l v^{(l)}\). The final linear layer multiplies this by a vocabulary-sized matrix \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{|V| \times d}\) to compute token logits.

In the usual view, we sum all layers and then compute token probabilities. But from a different perspective, each layer output \(v^{(l)} \in \mathbb{R}^d\) can be interpreted as pushing token logits upward by \(W v^{(l)} \in \mathbb{R}^{|V|}\) on its own. In particular, an intermediate neuron \(i\) in a 2-layer MLP connects to the i-th column of the second-layer parameter matrix, \(u^{(l)}_i \in \mathbb{R}^d\). When this neuron fires, token logits are pushed upward by \(W u^{(l)}_i \in \mathbb{R}^{|V|}\). This makes each neuron’s contribution to the output concrete.

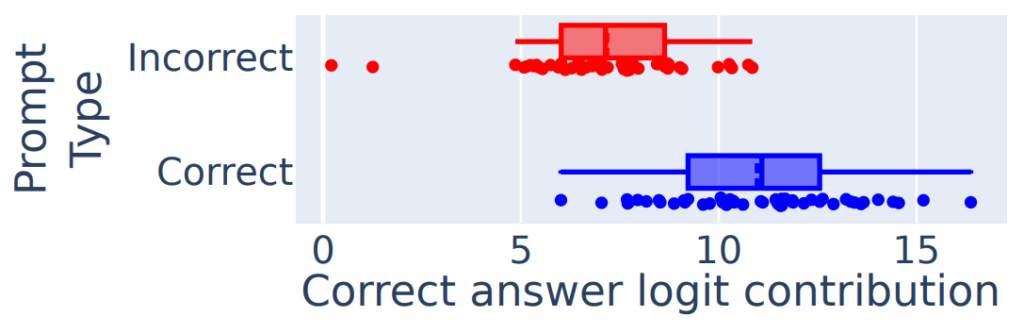

With this framework, we can also analyze why an LLM makes mistakes. Llama3-8B sometimes produces incorrect results. By comparing neuron firing patterns between correct and incorrect cases, the authors found that when the model makes a mistake, there is less logit boosting of the correct token by heuristic neurons.

As a result, the correct token is not fully highlighted, and the model ends up producing the wrong answer.

Arithmetic may feel like a trivial task, but even for such a simple task, LLMs solve it in an unexpected way, and digging into it reveals many interesting things.

Conclusion

This paper analyzes arithmetic as a representative reasoning task, but it is possible that for general reasoning tasks, LLMs also reason in a similar way.

Even if a conversation between you and ChatGPT looks like it arrives at a convincing conclusion, the AI might be reaching that conclusion via a creepy internal process like this.

I hope this article serves as a trigger to think more about the reasoning capabilities of LLMs.

Author Profile

If you found this article useful or interesting, I would be delighted if you could share your thoughts on social media.

New posts are announced on @joisino_en (Twitter), so please be sure to follow!

Ryoma Sato

Currently an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Informatics, Japan.

Research Interest: Machine Learning and Data Mining.

Ph.D (Kyoto University).