Sorting is a classic task in computer science, but it has recently intersected with state-of-the-art LLMs and sparked a new research trend.

Sorting can be executed as long as you define a comparison function. Traditional comparison functions assumed measurable numeric quantities such as height, price, or distance. However, if we call an LLM inside the comparison function, we can compare subjective and vague concepts such as “which one I prefer”, “which one is better”, or “which one is more relevant to the query”, enabling sorting based on these notions.

In Python, you can implement a function cmp that takes two objects a and b, outputs -1 if you want to place a before b, and outputs +1 if you want to place b before a. Then you set functools.cmp_to_key(cmp) as the sorting key to sort by any criterion.

First, let’s look at some applications to get the feel of it.

Sort papers by my preference

For example, the following code can sort papers in the order of my preference.

import functools

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

def cmp(a: dict, b: dict) -> int:

prompt = f"""Compare the following two papers and choose the one that better matches my preferences.

My preferences:

- I like papers that answer "why"

- I prefer technically non-trivial ideas over obvious combinations of standard techniques

- I like general-purpose technical techniques that remain useful over a long time

Papers I especially liked among what I have read:

- Adversarial Examples Are Not Bugs, They Are Features

- Physics of Language Models: Part 2.1, Grade-School Math and the Hidden Reasoning Process

- The Platonic Representation Hypothesis

- Language Models Learn to Mislead Humans via RLHF

- Arithmetic Without Algorithms: Language Models Solve Math With a Bag of Heuristics

The output must be exactly one character: either A or B.

[Paper A]

Title: {a['title']}

Abstract: {a['abstract']}

[Paper B]

Title: {b['title']}

Abstract: {b['abstract']}

"""

r = client.responses.create(

model="gpt-5-mini",

input=prompt,

)

ans = (r.output_text or "").strip().upper()

return -1 if ans == "A" else 1

# papers is a list of dicts

ranked = sorted(papers, key=functools.cmp_to_key(cmp))

When I sorted the oral papers accepted at ICLR 2026 with this, I obtained the following results.

How Do Transformers Learn to Associate Tokens: Gradient Leading Terms Bring Mechanistic Interpretability Verifying Chain-of-Thought Reasoning via its Computational Graph The Spacetime of Diffusion Models: An Information Geometry Perspective From Markov to Laplace: How Mamba In-Context Learns Markov Chains Energy-Based Transformers are Scalable Learners and Thinkers The Shape of Adversarial Influence: Characterizing LLM Latent Spaces with Persistent Homology Temporal superposition and feature geometry of RNNs under memory demands Sequences of Logits Reveal the Low Rank Structure of Language Models Distributional Equivalence in Linear Non-Gaussian Latent-Variable Cyclic Causal Models Reasoning without Training: Your Base Model is Smarter Than You Think . . .

Papers that match my taste are selected at the top. This should make it easier to decide what to read next.

Sort news from optimistic to pessimistic

If you implement the comparison function with a prompt like “Compare the following two economic news items and decide which one is more ‘optimistic'”, and then sort recent economic news headlines from the most optimistic to the most pessimistic, you get the following results. Here are the top 10 and bottom 10.

Inflation: Japan improves. Europe sees a gradual recovery, and the US sees a strong recovery. Stock and metal markets hit all-time highs. Dow Jones closes above 50,000 for the first time, on optimistic views about the US economic outlook Dow 50,000: AI changes the drivers; Caterpillar stands out with stock price doubling Nikkei average hits record high, closing up 2,065 yen at 54,720 yen; semiconductor rally reignites In 2026, Japanese stocks are expected to be driven by a turn to positive real wage growth and "higher ROE"; a "shift into Japanese stocks" by retail investors is also anticipated Dow surpasses 50,000 for the first time; leadership shifts from tech to manufacturing and resources Dow rises 515 points; manufacturing sentiment far exceeds market expectations Google's parent posts quarterly results with 30% profit increase; AI-related business is strong Amazon posts quarterly results with higher revenue and profit; core businesses such as cloud are strong TSMC to produce advanced 3nm semiconductors in Kumamoto; performance and use cases are . . . Russia's GDP growth slows sharply: from over 4% to +1.0% in 2025; domestic demand stagnates and inflation hits 9% amid the invasion of Ukraine Engel coefficient in 2025 hits highest level in 44 years; real consumer spending in December down 2.6% Bitcoin is on the brink of extinction... why a long "winter" is expected China's growth rate is "actually far below 5%": Wu Junhua President Zelensky condemns Russian attacks: "They prioritize only war" China rushes "war preparations" shock; deflation acceleration is unavoidable Japan's financial crisis, almost identical... three risks of worsening US-China relations that could hit China's cliff-edge economy bloated with debt China that Japan must know now: China's economy faces risk of entering a deflationary spiral; weak domestic demand and population decline also weigh "There is no exit..." the decisive reason China's deflation is more severe than Japan's "lost 30 years" [China's economy in 2026] A time bomb toward collapse... a crisis where even SOEs are abandoned; a wave of real-estate and construction firm failures leading to a financial crisis

When sorting 295 news headlines, the sort performed 2,324 comparisons and finished in about 2.5 minutes. Using GPT-5-mini (with thinking enabled) cost $0.85. Using GPT-5-nano reduces the cost to about one fifth.

Beyond this, you can sort politicians from left to right, sort bug reports by severity, and more. Even for tasks that require subjective and vague judgments, you can easily sort by using an LLM.

One strength is that you can plug this into traditional sorting in a plug-and-play manner. However, the cost of calling an LLM differs from the computational models assumed by traditional sorting algorithms, so new sorting algorithms that assume LLM-based sorting are starting to be proposed. In this article, I introduce this trend.

Listwise and pairwise: naive approaches

If you try to do sorting with an LLM in the most naive way, you would pass all items to the LLM and ask it to reorder them and output the result. This approach, where you input all items at once, is called the listwise method. For example, RankGPT [Sun+ EMNLP 2023] is a method where you assign numbers to items and ask the model to output the reordered numbers. It uses a prompt like the following.

Below are {{num}} items, each indicated by a numeric identifier in []. Reorder them according to the criterion "XXX".

[1] {{item_1}}

[2] {{item_2}}

...

[8] {{item_8}}

Output a descending list using the identifiers, showing the best item first. The output format must be [] > [] > ... (e.g., [1] > [2] > ...).

Then the LLM outputs something like:

[8] > [3] > [1] > [5] > [2] > [4] > [6] > [7]

and you can use this output directly as the sorting result.

The advantages of the listwise method are that it requires only one call, and that within the same prompt it can see multiple candidates at once, so it can leverage more information and perform context-aware comparisons.

On the other hand, the downside is that it is hard to stabilize the output. In particular, as the number of items increases, both the input and output become longer, and the task per call becomes harder, so it breaks more easily. For example, output errors such as missing items, duplicated items, or unparseable formats occur frequently. If the number of items is on the order of dozens, you can often manage, but once it exceeds a few hundred, naive listwise methods become difficult. If you are discarding the result after a single use, this might not be a major issue, but naive approaches are not suitable for stable production services.

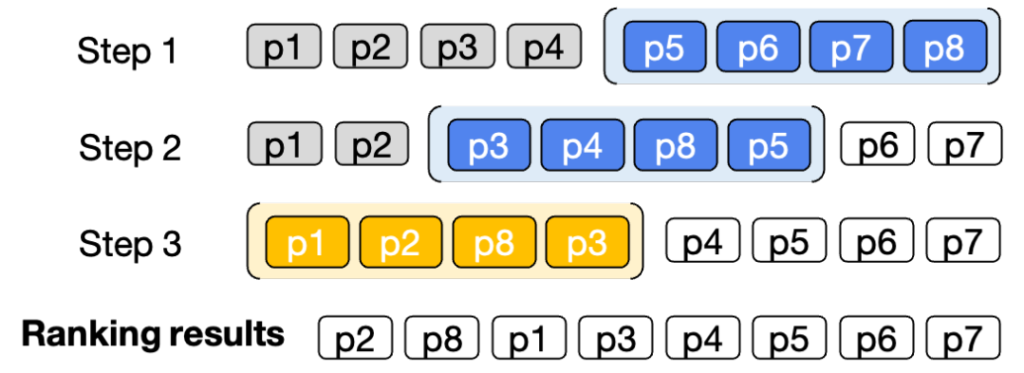

In practice, when the number of candidate items is large, you often cannot input all items at once, so approximate processing is commonly used. The most widely used approach is the sliding window method.

First, prepare an item sequence sorted by a simple criterion such as a rule-based method. Feed the bottom \(w\) items into the LLM and reorder them. Next, slide the window upward by \(w/2\) items and reorder again. Repeat this until you reach the top. This performs reordering with \(O(n/w)\) LLM calls. This is not a perfect sort, but it can surface items missed by classical criteria via LLM comparisons, while avoiding the \(O(n \log n)\) comparisons required for strict sorting. As a compromise, it is popular. In particular, for use cases like search reranking where strict sorting is not required and you only want to refine the top results, this approach is effective.

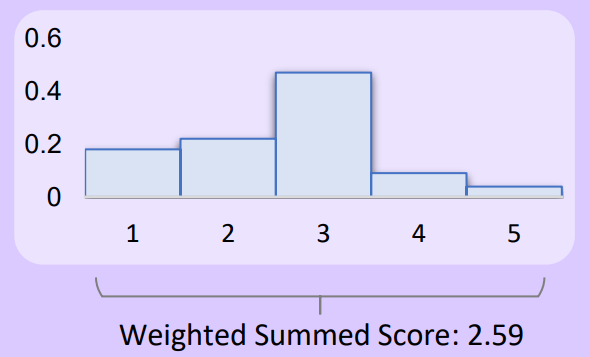

At the opposite extreme of the listwise method is the pointwise method. In the pointwise method, you input each item independently and have the LLM output a score for it. For example, you can use a prompt like the following.

Evaluate how well the following paper matches my preferences on a scale from 1 to 5.

Title: {title}

Abstract: {abstract}

Score (1-5):

If you let the LLM continue, you get something like:

3

Then you can use this score as a key and run a conventional sorting algorithm. However, if you only output integers from 1 to 5, many ties occur. To avoid this, a method has been proposed that uses the output probabilities of each number token for weighting [Liu+ EMNLP 2023].

\[\text{score}(x) = \sum_{i = 1}^5 i \times P(\text{LLM output “} i \text{”} \mid x)\]

This captures subtle nuances even when the LLM is uncertain between, say, giving 2 or 3 points, enabling finer-grained scoring.

The advantages of the pointwise method are that it requires \(n\) calls and, compared to listwise methods, it breaks less as the number of items increases. The disadvantage is that designing an absolute scale is difficult. In the pointwise method, you score an item without seeing the other items. Ideally, if rivals are low-quality you can score more leniently, and if rivals are all high-quality you should score more strictly to make distinctions. But independent scoring cannot incorporate this. The criterion can drift between calls, and items scored when the LLM happens to be “in a generous mood” can rank higher by chance.

Compared to these, the method described at the beginning, where you present two items and ask which is better, is called the pairwise method. The merit of the pairwise method is that comparison is easier than absolute evaluation or reordering everything at once. Even for humans, it is easier to compare two items than to assign an absolute score or reorder everything at once. The same holds for LLMs: relative comparison is easier and more stable. This is especially pronounced when differences are small and you must capture subtle nuances.

Also, the history of sorting algorithms is long, and there are many algorithms and analyses beyond naive sorting, such as parallelizability or approximate comparison settings. A further advantage of the pairwise method is that it can benefit from these results.

Setwise method

The setwise method sits between pairwise and listwise methods. In the setwise method, you compare \(c\) items together and ask for answers such as “which is the best” or “where should this be inserted”. This reduces the number of LLM calls because a single call can perform multiple comparisons. Since LLM costs are strongly dominated by the number of calls, call-reduction methods like this are effective.

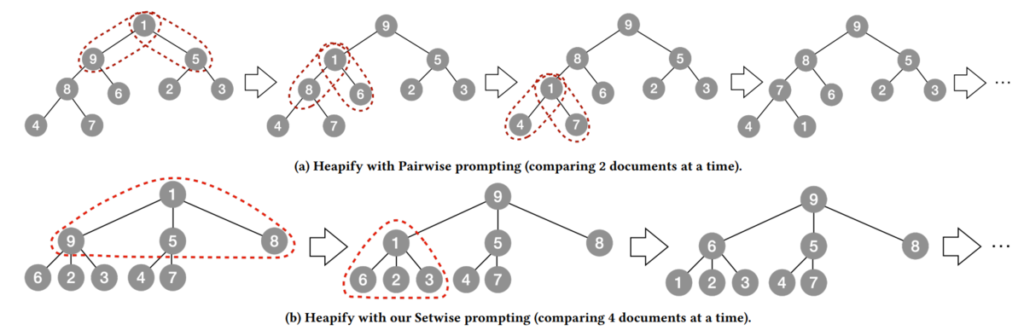

For example, conventional heap sort typically uses a binary heap (a binary tree). This is natural because in classical computation models, comparing \(c\) items costs \(\Omega(c)\), so comparing two items at a time makes sense. In contrast, an LLM can compare both two items and \(c\) items in a single call, and the cost does not change much. Therefore, conventional binary-heap-based methods may be suboptimal. Zhuang et al. [Zhuang+ SIGIR 2024] focused on this and proposed using a \((c – 1)\)-ary heap instead of a binary heap in heap sort, comparing a node with all its children in a single LLM call to reduce the number of calls. This cuts the cost by about half while maintaining performance.

Handling contradictions

LLM-based evaluation is powerful, but LLM outputs are not guaranteed to be consistent, and they can violate the axioms of order. Sorting algorithms basically assume the following axioms hold.

- Antisymmetry: if \(x_i \succ x_j\) and \(x_j \succ x_i\), then \(x_i = x_j\)

- Transitivity: if \(x_i \succ x_j\) and \(x_j \succ x_k\), then \(x_i \succ x_k\)

- Completeness: either \(x_i \succ x_j\) or \(x_j \succ x_i\) holds

However, LLM responses do not necessarily satisfy these axioms.

An LLM’s positional bias can cause issues for antisymmetry and completeness. When doing a comparison, an LLM can be biased toward choosing the option shown first. For example, Zheng et al. [Zheng+ NeurIPS Datasets 2023] asked GPT-4 which output was better, GPT-3.5’s or Vicuna-13B’s. When GPT-3.5’s output was presented first, GPT-4 chose GPT-3.5; when Vicuna-13B was presented first, GPT-4 chose Vicuna-13B. In other words, GPT-4’s answers were not consistent, and in this case you cannot determine which is better. If you use an LLM as a comparison function without accounting for this, elements that happen to be shown first more often can gain an unfair advantage. To mitigate this bias, a method has been proposed that calls both llm(a, b) and llm(b, a), declares \(a \succ b\) only if \(a\) is chosen consistently, declares \(b \succ a\) only if \(b\) is chosen consistently, and treats it as a tie if the results conflict [Qin+ NAACL 2024]. For ties, you can use a sorting algorithm that handles ties, or fall back to another criterion.

Because LLM outputs are not transitive, in a strict sense you cannot sort. If the LLM says B is better than A, C is better than B, and A is better than C, then no matter which you place first, you create an inconsistency. If you run sorting without considering this, depending on the sorting algorithm, it might not work at all, or it might not terminate. Sorting without transitivity corresponds theoretically to the feedback arc set problem on tournaments [Ailon+ JACM 2008]. This problem asks: given \(n\) elements and \({n \choose 2}\) pairwise comparison results among them, find an ordering that agrees with as many comparisons as possible. The comparison results may be non-transitive, and in that case you want to minimize the number of contradictory comparisons. The problem is NP-hard, but it is known that if you run quicksort naively, it becomes a good approximation algorithm with expected approximation factor 3 (that is, on average, the number of contradictory pairs is at most 3 times the optimum) [Ailon+ JACM 2008]. Concretely, you choose a pivot uniformly at random, partition elements into left and right using only comparisons against the pivot, and recursively sort each side. This method is called KwikSort (a pun on QuickSort). In traditional sorting, transitivity often holds, so you do not think about this much, but with LLMs transitivity does not hold, so using sorting algorithms with such properties is effective.

Considering parallel execution

When using LLMs, batch size is also important. GPUs have high parallel execution capability, so the processing time with batch size 1 and batch size 2 often does not differ. Therefore, if you can bundle multiple comparisons into a batch request, efficiency improves. In heap sort, the next comparison targets depend on previous results, so batching is difficult. In contrast, quicksort can compare the pivot with \(x_1\), the pivot with \(x_2\), …, the pivot with \(x_n\) all in parallel. If the degree of parallelism is high enough to run \(n\) comparisons simultaneously, you can speed up by up to a factor of \(n\), and complete the sort in \(O(\log n)\) batch calls. With APIs, you may not reduce cost, but by issuing multiple requests simultaneously you can reduce latency.

Leveraging imperfect comparisons

LLM calls are inevitably costly. Therefore, methods are also being developed that leverage low-cost comparisons such as rule-based methods, calling the LLM only when necessary to reduce cost.

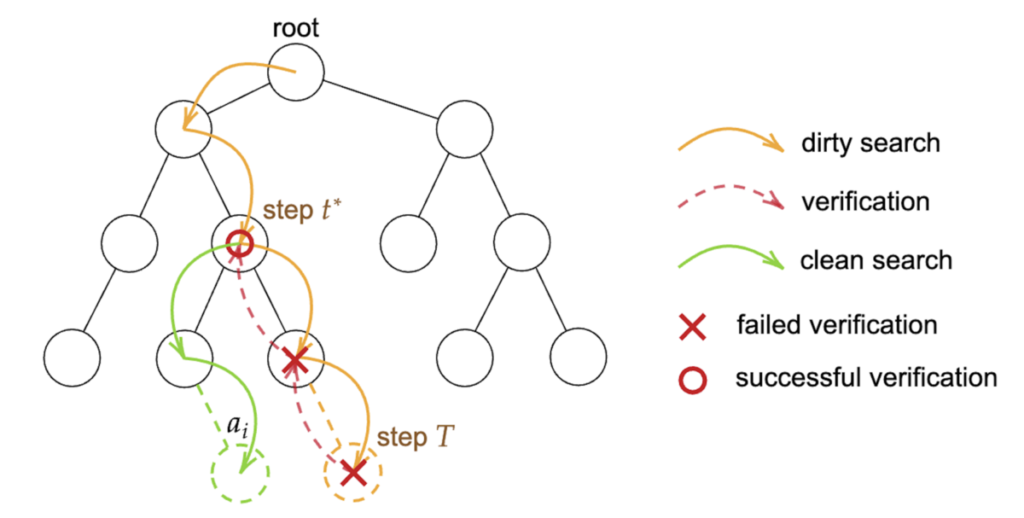

Theoretically, this corresponds to Sorting with Predictions [Bai+ NeurIPS 2023]. This work considers two problem settings to achieve strict sorting under the main comparison function. The first setting assumes you have access to a “dirty” comparison function. This function is free to call, but it is not guaranteed to match the main comparison function. The goal is to leverage this dirty comparison while ultimately producing the exact order according to the main comparison function. The second setting assumes you are given predictions of each element’s position. The predictions are not guaranteed to be accurate, but you leverage them while still aiming for exact sorting according to the main comparison function. Bai et al.’s method achieves the ideal result in both settings: when predictions are good, it completes sorting with only \(O(n)\) calls to the main comparison function; in the worst case where predictions are adversarial, it still matches the no-prediction baseline with \(O(n \log n)\) comparisons. For example, in the first setting, they build a balanced binary search tree using the main comparison function. When a new item arrives, they first use the dirty comparison function to estimate the insertion position in the tree. Then they validate the dirty comparisons using the main comparison function while climbing from the leaf upward, correcting the insertion position and re-inserting accurately.

If the dirty comparison function has reasonably high quality, the first stage identifies an approximately correct position, and only local fixes are needed, so insertion completes in constant time. Even if the dirty comparison is completely random, you only re-validate from leaf to root and descend to a new leaf, so insertion still completes with at most twice the \(O(\log n)\) comparisons. In LLM-based sorting as well, you can use a simple rule-based comparison function as the “dirty” comparator to assist the LLM-based main comparison, keeping LLM calls minimal while still obtaining high-quality rankings.

Summary

So far, I have introduced various design principles for sorting algorithms that use LLMs. If you want to try it in practice, I recommend starting with either the sliding window method or quicksort (KwikSort). For tasks like search reranking where strict sorting is not needed, the sliding window method is sufficient to refine the top results. For tasks like sorting by stance in economic news or political ideology, where the ordering across both sides and the center matters, using quicksort to sort the whole list is better. In particular, quicksort has theoretical guarantees even when transitivity does not hold, and it supports parallel execution, so it matches LLMs well. If you want to push further, incorporating the design techniques introduced in this article should help.

Closing

Sorting is often seen as a mature technology, but it is actively evolving as it intersects with state-of-the-art LLMs. With LLM sorting, tasks that were difficult with previous methods, such as ranking papers, sorting economic news by stance, or sorting political ideology, can be achieved without developing specialized models, using only LLM calls. Sorting is just one example of a classic computer science task, and this trend of leveraging LLMs will expand beyond sorting to many other classic problems. I hope this article helps you understand this trend.

A comprehensive survey is available at A Survey on Sorting with Large Language Models.

Author Profile

If you found this article useful or interesting, I would be delighted if you could share your thoughts on social media.

New posts are announced on @joisino_en (Twitter), so please be sure to follow!

Ryoma Sato

Currently an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Informatics, Japan.

Research Interest: Machine Learning and Data Mining.

Ph.D (Kyoto University).