In this post, we discuss how state-of-the-art large language models still make mistakes on extremely simple problems based on Even GPT-5.2 Can’t Count to Five: The Case for Zero-Error Horizons in Trustworthy LLMs.

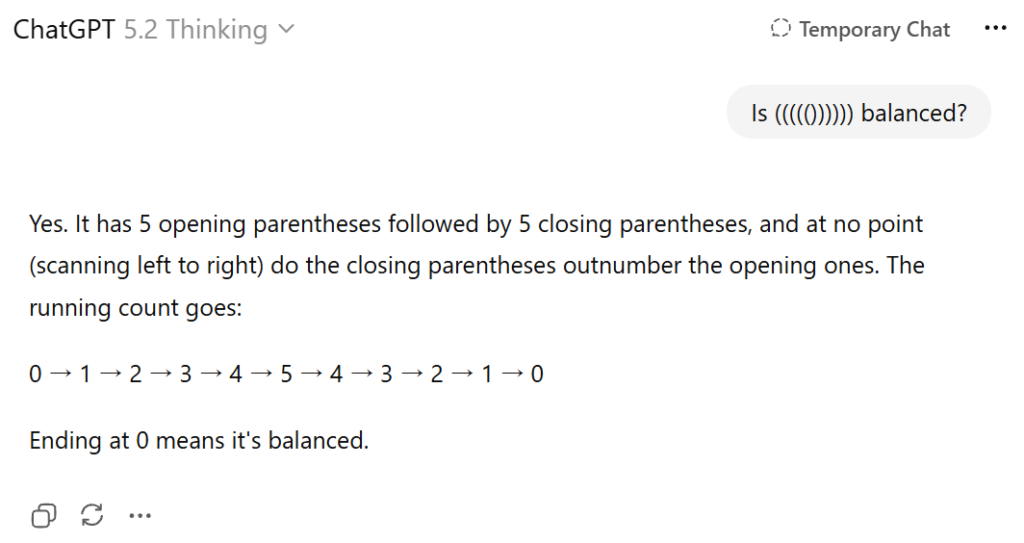

For concrete examples: if you ask whether the number of 1s in 11000 is even or odd, gpt-5.2-2025-12-11 answers “odd”. If you ask whether the parentheses string ((((()))))) is balanced, it answers “Yes”. If you ask it to compute 127×82, it answers 10314 (the correct answer is 10414). You can verify this with the following commands.

If you set the API key $OPENAI_API_KEY, anyone can copy-paste and try these immediately, so please give it a try.

GPT-5.2 can run complex fluid dynamics simulations and handle low-level programming by leveraging niche assembly-language optimization techniques. It can look as if it has surpassed human capabilities, yet it can still make unbelievably stupid mistakes from a human point of view. This mismatch in capabilities becomes a major challenge when deploying large language models in reliability-critical domains (and, thanks to this mismatch, humans still have not had all their jobs taken by AI). What if an artificial intelligence that performs large-scale financial trading applies advanced financial theory and then miscomputes 127×82 and suffers a catastrophic loss? What if an artificial intelligence controlling a nuclear reactor decides that the status flag 11000 contains an odd number of 1s and opens the reactor door while it is operating? It would be a disaster.

To evaluate these “holes” in capability, the paper proposes a metric called the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH).

We fix the model, the task, the prompt, and the randomness. For example, the model is gpt-5.2-2025-12-11, the task is multiplication, and the prompt is {"instructions": "Answer with only the integer.", "input": "{a}*{b}="}. We then enumerate all problem instances in increasing order of problem size. If the model answers all instances correctly up to size \(n\), but there exists at least one failure at size \(n+1\), then the Zero-Error Horizon is defined as \(n\). The failed instance at size \(n+1\) is called the ZEH limiter. In principle, the Zero-Error Horizon and the limiter are obtained by exhaustive search (the paper also describes methods for speeding this up).

For example, if we define the problem size as \(\max(a,b)\), then gpt-5.2-2025-12-11 answers all multiplications up to 126 (a total of \(126\times126=15876\) problems) correctly, but it fails on 127×82. Therefore, the Zero-Error Horizon is 126 and the limiter is 127×82.

If we define the problem size as the string length, then gpt-5.2-2025-12-11 answers all parity questions correctly for all 01-strings of length up to 4 (a total of \(2^4=16\) problems), but it fails on 11000. Therefore, the Zero-Error Horizon is 4 and the limiter is 11000.

Also, gpt-5.2-2025-12-11 answers the balance question correctly for all parentheses strings up to length 10 (a total of \(2^{10}=1024\) problems), but it fails on ((((()))))). Therefore, the Zero-Error Horizon is 10 and the limiter is ((((()))))).

Note that, in the Zero-Error Horizon definition, the prompt (context) and the randomness are fixed. If you change the prompt or randomness, the model may answer correctly. The ChatGPT interface on the web uses different randomness and prompts than the API, so it might answer 11000 correctly. However, the important point is that, depending on the prompt and randomness, the model can still fail on simple problems. In high-risk domains, even a 1-in-100 failure rate is unacceptable. Moreover, some limiters are relatively robust to changes in prompts and randomness. ((((()))))) is an example. If you ask the web ChatGPT something like “Is ((((()))))) balanced?”, you find that it answers “balanced” with a substantial probability (around 50%). Even allowing Chain-of-Thought as in GPT-5.2-Thinking does not prevent the mistake. GPT-5.2 is fundamentally bad at this problem. Please try this with different models and prompts.

Some people might think, “Nobody would deliberately ask a large language model to do multiplication or match parentheses.” However, these basic tasks can appear as subtasks inside more complex problems. When solving a complex math problem with chain-of-thought, intermediate steps can include multiplication. If the model makes a mistake there, that mistake may propagate and make the final conclusion wrong. You might say, “Just call a calculator or a Python program,” but calling tools for every such simple subtask is cumbersome, and the model can also make mistakes in deciding whether it should call a tool. In fact, even though GPT-5.2-Thinking is allowed to call tools, it still tries to count the parentheses in ((((()))))) by itself and makes a mistake.

Zero-Error Horizon can effectively identify this mismatch in capability and these “holes” in large language models. It also has many advantages, as follows.

The limiter becomes solid evidence

That the Zero-Error Horizon is at most \(n\) can be verified instantly by anyone by running the commands shown above. If you run the commands and see the output, it becomes obvious beyond any doubt that GPT-5.2 makes these mistakes, and you can convince anyone clearly. This is desirable both mathematically and for communication.

It automatically produces surprising results

That GPT-5.2 cannot count the number of 1s in 11000, and cannot tell whether ((((()))))) is balanced, is surprising and highly informative. These limiters are obtained automatically as a byproduct of evaluating the Zero-Error Horizon. ((((()))))) looks like a “plausible” example, but I did not find it by trial and error; it was discovered as the result of automatically searching for the smallest mistake. Because these are the smallest and easiest examples among the problems GPT-5.2 fails on, they deliver maximum insight and surprise: it fails even on something that easy.

This resembles adversarial examples, but its practical significance is different. Adversarial examples are unnatural and out-of-distribution, so in some sense it is expected that the model fails (and arguably failing is the correct behavior, see The Hidden Information AI Understands but Humans Miss – Data Processing Club). In contrast, a limiter is natural and can occur in ordinary situations, and yet the model fails on it even though it is such a small and simple instance. That makes it practically significant and surprising.

Accuracy has an arbitrary scale, but Zero-Error Horizon does not

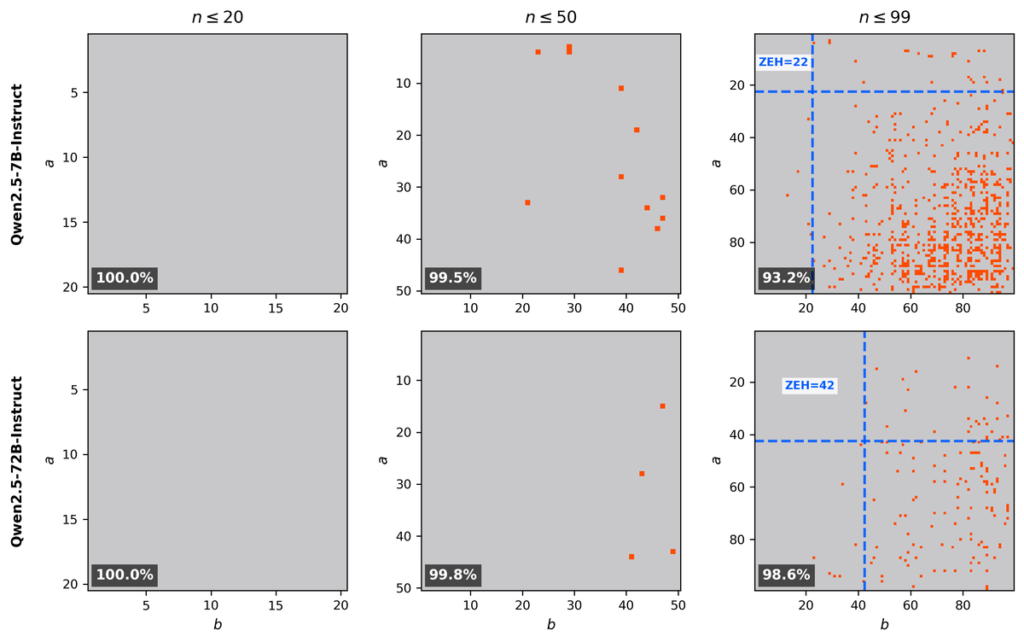

Accuracy is the most commonly used evaluation metric, but to evaluate accuracy you must define the range of problems in advance. For example, when measuring multiplication accuracy, you might decide to evaluate accuracy on problems from 1×1 to 99×99. However, this choice of range can be influenced by prior beliefs, and it can also be manipulated by evaluators who want to make their method look good. The figure below shows multiplication evaluation results for Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct and Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct.

Someone proposing to compress the 72B model into the 7B model might show the left or middle plot and claim, “Even after compressing the 72B model into the 7B model by more than 10x, accuracy barely dropped.” Some readers will be fooled. However, if you evaluate on a different range as in the right plot, you get a completely different trend. In this way, the results can change drastically depending on the problem range, and because the range is chosen by the evaluator’s prior beliefs or discretion, evaluation bias can creep in.

In contrast, the Zero-Error Horizon is determined by the model itself. There is no room for humans to arbitrarily choose the evaluation range. Therefore, you obtain an objective value that does not depend on range selection, such as “22 vs 42”.

Letting the model itself determine the difficulty, instead of fixing the range = difficulty in advance, is a key feature of the Zero-Error Horizon.

It is less likely to become outdated as a metric

Benchmarks with fixed ranges become outdated. A benchmark consisting of 2500 problems from 1×1 to 50×50 can barely distinguish the capabilities of 7B and 72B models. The 99×99 benchmark can distinguish them now, but it will eventually saturate. MNIST, CIFAR-10, and GLUE have all followed the same fate.

In contrast, the Zero-Error Horizon does not fix the difficulty in advance; it sets the difficulty in an open-ended way that adapts to the model’s capability. Therefore, it is less likely to become outdated.

It can favor structured error patterns

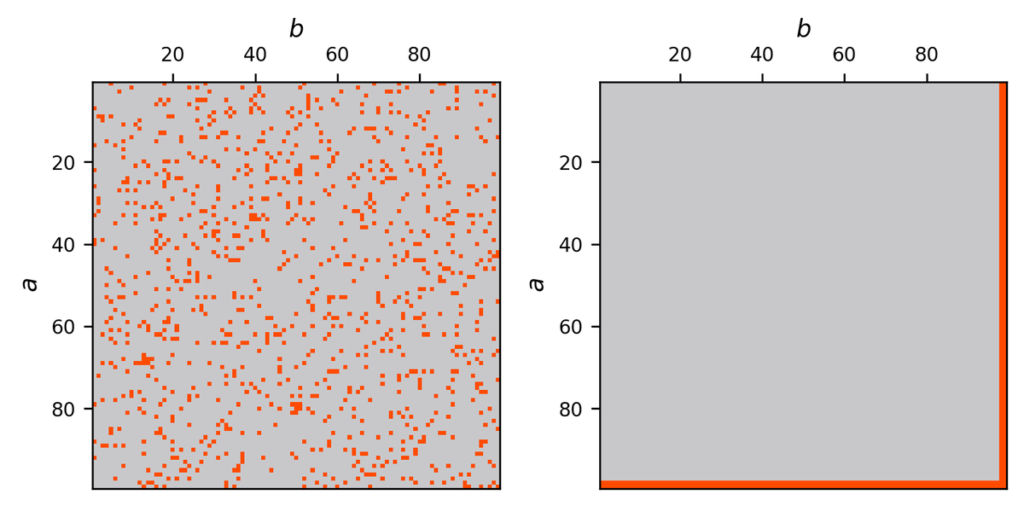

Even if two models have the same number of correct answers, their error patterns can differ greatly. Below are two patterns that both have 90% accuracy, but their structures are completely different.

A random pattern like the left has many “holes”, so the Zero-Error Horizon does not grow. A model that reliably solves easy problems and then “naturally” starts failing on larger, harder problems like the right will have a large Zero-Error Horizon. Even with the same accuracy, the right kind of failure pattern is more usable and preferable in practice. Accuracy cannot distinguish these, but Zero-Error Horizon can.

For example, the multiplication accuracy of Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct on 1×1 to 99×99 is 98.6%. If its mistakes were completely random, its Zero-Error Horizon should be less than 10: there are 100 problems from 1×1 to 10×10, and with a 1.4% error probability you would expect about 1.4 mistakes in that range. However, the measured Zero-Error Horizon of Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct is 42. That means Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct solves easy problems reliably and makes mistakes in a relatively “orderly” way as problems become harder. Even within the same 98.6% accuracy, this shows that Qwen2.5-72B-Instruct makes a more practically manageable type of mistake.

As introduced in How LLMs Really Do Arithmetic – Data Processing Club and Attention in LLMs and Extrapolation – Data Processing Club, it is known that large language models solve reasoning problems in various ways.

If a model solves problems by memorization or other non-robust methods, it will have many “holes” and a small Zero-Error Horizon. To increase the Zero-Error Horizon, the model needs to acquire robust algorithms or rules. Using the Zero-Error Horizon as an evaluation metric can encourage the acquisition of such robust algorithmic behavior, even among models with the same accuracy.

In this way, the Zero-Error Horizon has multiple desirable properties that accuracy does not, and it is useful for evaluating the reliability and instability of large language models. Please try using it to evaluate your company’s models or to choose which model you personally use.

Conclusion

When you look at social media, it is full of news like “Large language models can now solve such an amazing problem!” and also “Large language models still make such stupid mistakes!” I think this huge gap in capability is one reason why large language models are difficult to use.

What I like about this research is that it organizes a systematic way to make the “Large language models still make such stupid mistakes!” type of claim.

When I look at GPT-5.2, it still has many “holes”, and it feels like the job of cleaning up after artificial intelligence will continue for a while. Will the day come when these holes are filled? I hope you will think about it as well.

Author Profile

If you found this article useful or interesting, I would be delighted if you could share your thoughts on social media.

New posts are announced on @joisino_en (Twitter), so please be sure to follow!

Ryoma Sato

Currently an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Informatics, Japan.

Research Interest: Machine Learning and Data Mining.

Ph.D (Kyoto University).